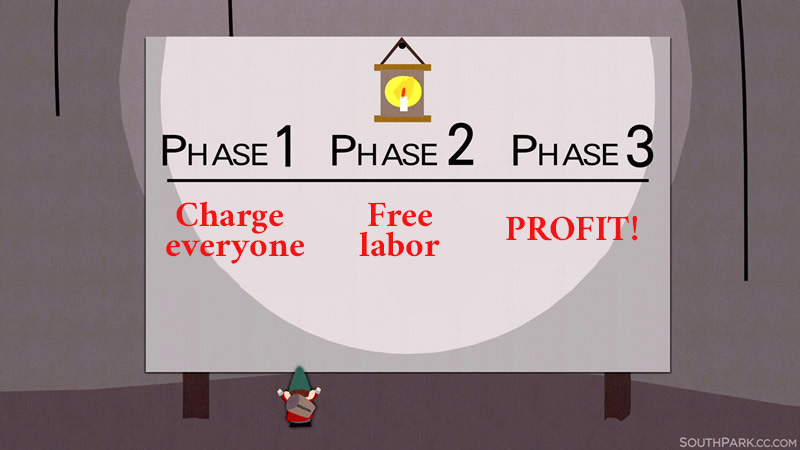

Welcome to Science with Shrike! Over the last two posts, you learned about the publishing enterprise, and how to score PIs and journals on publications without needing to know any science! With that foundation, we’re ready to talk about publishing models, because this governs access to published work, and is where lots of money is made in science. Remember, in academia, scientists pay journals to publish their research, scientists provide peer review and editor work to the journal for free, and the journals charge a subscription fee for journal access. Also remember from the last post that publishers sometimes run a lot of journals directly, and sometimes take a “white-label” approach to journal creation. We’ll start by covering journal access and how journals and publishers work ‘under the hood’.

How do readers access journal articles?

Unlike newspapers and magazines, where the customers are individuals, the primary customers for a scientific journal are a group of customers at a few institutions. Consequently, while scientific journals often provide individual subscriptions, most scientists get their access via their institution, which pays the journal for institutional access. This simplifies the process and benefits all sides: the journal only has to sell to a few customers, and can charge more per sale, while the scientists ostensibly get some negotiating power (and can delegate the contract negotiations to university/library officials). Academics are terrible when it comes to paying for things anyways, so the journals make more money charging the universities than they would trying to sell individual subscriptions to the scientists (hint: the academics would get one subscription and share with everyone they don’t hate). While journals usually sell subscriptions, they also sell individual articles a la carte. Shrike honestly has no idea if anyone pays for individual articles, or if the high prices are just meant to encourage journal subscription. Shrike has never paid ala carte for an article because there are too many ways to get the article for free.

So how does one get a journal article for free? There are several ways. Interlibrary loan is one route. Sometimes there is a charge for this, but that depends on institution, and even then it’s a fraction of what the journal would ask. The downside is you get no supplemental data. Another way is to cold email the corresponding author and ask for a pdf of the article.

Another option is Pubmed Central (LINK). Congress decided that if taxpayers fund research, they should not have to pay to access that research. Consequently, all research published with NIH funding must be made publicly accessible within a year after publication, and deposited into a central database called Pubmed Central. This compromise lets the journals still earn money (science is WAY too competitive to wait 6 months to a year to learn about new results, so institutions still have to pay for access), and lets the public have free access. Several other funders have enacted similar provisions. This has been part of a push for “Open Access”, where people do not need to pay to access journal articles.

One Communist, Alexandra Elbakyan, has also provided a more straightforward approach to “Open Access”. She developed a database called “Sci-hub” that provides free access to journal articles without regard for copyright. It’s something of a ‘pirate bay’ for science articles, though the database is very centralized under Elbakyan’s control. Since she lives in Kazakhstan, Elsevier and the American Chemical Society have had trouble collecting the millions of $US Trash Tokens worth of damages they’ve won in court, and she has not been extradited to the US. Similar to other pirate websites, Sci-hub changes domains fairly frequently as the old ones get targeted. Since there’s no need for a paywall, it is usually faster to paste the DOI into Sci-hub than to log-in to the journal to which you have legit access, and then find the article you want. Despite the court cases, Shrike is not clear on the actual impact of Sci-hub on the academic publishing enterprise: institutions still pay for access and do not encourage Sci-hub use.

Finally, Open access is a legit way to read journal articles for free without coercion by government or piracy. Open Access is an alternative to the subscription model that completely disrupted academic publishing. In Open Access, instead of paying page charges, authors pay a one-time fee to make the paper free for everyone to access. This one-time fee usually runs $2000-$5000 per article. Due to the success of Open Access, few journals run as purely subscription based approach anymore. Most journals run as a hybrid ‘subscription/open access’, where authors decide if they want to pay the extra money to make their article Open Access or not. The pro for the author is free access = more readers. The con is that it costs a lot more, and grant funds are often limited.

Journal business model

From a journal point of view, Open Access changed a lot of things in the industry, which itself was a consequence of digital publishing. In the old days, you needed a print journal to be considered a real journal, but those days are gone. Online only is now an acceptable venue, which means all you really need is a website, and data hosting. There are a lot of apps and work that also goes into the journal process, but the overhead is significantly lower than it used to be. A journal needs a domain, email, manuscript submission system (these are usually third party, like eJournalPress), DOI registration, long-term storage, content editors, copy-editors, peer reviewer database and institutional payment processing. There’s also the journal policies that need to be sorted out.

There are two main approaches to creating a journal. The first is academic-led. Academics in a new/under-studied field want a journal focused on their area of expertise. No more sifting through ten different journals to find the relevant work in the field; concentrate it all in one place. This also improves rigor since you reduce the chance the work goes to someone who doesn’t know the field as well. The Journal of Extracellular Vesicles is one example of a journal like this (LINK). People working on microvesicles formed a scientific society, and then got a journal set up to publish work on that topic. Since they were scientists, they didn’t really want to spend a lot of time on the business of setting up a journal, so they partnered with Wiley, who handles a lot of the hosting, analytics and some advertising. However, it is important to remember that journals are all fundamentally a commercial enterprise. Academics often forget that this holds as true for society journals as it does for overtly commercial organizations like Springer-Nature, Elsevier or Frontiers.

The other approach to creating a journal is publisher-led. Frontiers, MDPI, PLoS, and Springer-Nature are examples of this approach. A business launches one or usually more journals, and recruits the needed academics to help lend the expertise as needed. Nature is one of the most valuable brands in scientific publishing, and keeps its own paid editorial staff. Frontiers and MDPI are more recent examples of journal launches. These vary in quality and prestige, as Frontiers and MDPI are borderline scam publishers that managed to have one or more legit journals take off. The main goal is to run several journals on the same platform to minimize overhead costs, and maximize profits. What people consider to be scam journals varies; some consider anything less than a fourth-tier journal to be a scam, some highlight the profit-motive, others are more concerned about poor/deceptive practices.

What makes a journal a predatory/scam journal?

A full article describing predatory journals/publishers is available at this LINK. The biggest issues are dishonesty, and lack of transparency. Predatory publishers do some or all of the following: lie about their editorial board (eg use prominent academics names/pictures to add legitimacy, or fake names), lie about peer-review (ie it doesn’t happen, or is very, very cursory), lie about affiliations with journal groups like Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), lie about their Impact Factor, name their journals very similar to prominent ones (eg Cells instead of Cell), hide Article Processing Charges (APCs), provide little to no copy-editing, lots of email advertising, and questionable publication practices (demand copyright at submission instead of at publication, publish prior to agreement, refuse to remove article at authors’ request, or removes articles arbitrarily). As mentioned last week, Jeffrey Beall used to keep a list of journals and publishers he thought fit. Since a lot of money was on the line, it eventually became too much trouble to maintain. As a positive alternative, groups like DOAJ formed to white-list journals, instead of blacklisting the predatory ones.

As with many other things, it is good to stick with the best projects/journals and not worry about the little ones. When starting out as a PI, helping with fourth tier journals may be worthwhile for the editorial/review experience, but hopefully you’ll move up to reviewing for/editing bigger journals. You also want to be very careful in lending your name to a scam journal. Some new projects are likely to have a high impact factor in a few years, and be easier to get into because they’re new. However, only the new ones from established publishers/academic groups are worth considering (eg a new Nature or Cell spin-off, or Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI)-led journal). Unlike crypto, new scam journals are extremely unlikely to “10x”. Just publish in PLoS One or Scientific Reports instead of the scam journal. Only publish in a new journal if the publishers are waiving the APC.

Unlike the underpants gnomes, publishers have a robust model that works.

Costs of running a journal

The warning about scams suggests there’s good money to be made in the scientific journal space. This really ballooned once a journal could leave printing behind, because that cut costs tremendously. Let’s look at the costs, which are primarily people and infrastructure. The infrastructure no longer includes print, so it’s just web-hosting, email, eJP, DOI, storage, payment processing and marketing. These are all fixed costs that can mostly be contracted out, and you get economies of scale when you launch 30-300 journals. People are the expensive part. However, content/copy editing is also pretty cheap these days, especially if you hire in China.

That leaves the cost of academic editors, and peer reviewers, who provide the key expertise for your journal. Tier 1 journals aside, they’re usually free, or close to it. Yes, academics have no clue how to value their time. At the better journals, there is some benefit for academics, because you learn about new science before it is published. As an editor, you also have some control over what gets out and what doesn’t get out. Sometimes journals will offer a free publication to reviewers, others use a voucher system to give you a discount on the next paper. Overall, reviewing and editing fall under the ‘service’ category on your CV because the time costs outweigh the benefits.

Peer review

The key to academic publishing is currently peer review. This is the system that sets scientific articles apart from opinionated bloggers and magazines. This is in many ways an ‘audit’ of the scientific advance done for the journal so that it can decide if this manuscript is going to add value to the journal, or not. Adding value for top journals is improving the journal metrics—will it be highly cited, will it be paradigm shifting, will it drive more traffic to the journal? Adding value for the Tier 4 journals is ensuring that it is technically correct, and unlikely to be retracted. Either way, independent review provides confidence that the results are technically correct, and are appealing to the journal’s readership. The peer review process works as follows: if the editor decides to send the manuscript out for peer review, the editor solicits 2-3 (sometimes only 1 in the scam journals) people who have expertise in that area to review the manuscript. The quality of experts scales with journal prestige—the most successful scientists peer review for Science, Nature, and Cell, while less successful ones review for lower tier journals. Tier 4 and below sometimes solicit post-docs to do the peer review (and scam journals may even ask graduate students!). While authors can propose reviewers and rule out reviewers, it is the editor who ultimately chooses who to solicit. Often editors respect author choices to varying extents. Pubilshers like Frontiers use AI to solicit peer reviewers and perform some basic journal checks if the human editor takes too long. The AI doesn’t select as well as a human, so it’s easier to get your paper accepted at journals doing this. It’s also worth noting that journals track reviewer metrics at their journal. If you do a good job reviewing, a bad job reviewing, take forever… it’s all tracked by the journal and available to the editors.

Once a reviewer is asked to review, the reviewer sees the title, authors and abstract before deciding to accept the review assignment or not. If the reviewer agrees, the reviewer has full access and needs to turn the review in. Two weeks is the standard at most journals, though MDPI pushes one week. Review forms vary by journal, but generally, the reviewer will summarize the work, put it in the larger context, and evaluate the strengths/weaknesses of the paper, including priority at higher journals. In addition to comments to the authors, the reviewer gives a confidential recommendation to the editor (Accept, Minor revision, major revision, reject), as well as any confidential comments. Based on the reviews, the editor decides what to do with the paper. It is not uncommon for a reviewer to get over-ruled by an editor. Also, journals track “time to first decision”, which is how long it takes from submission to informing the authors of the results of the first round of peer review, and “time to publication”. To shorten “time to publication”, some journals have started to reject papers that need major revisions, but suggested that the paper could be resubmitted. This makes the journal stats better: doubles the submissions, increases the failure rate, and shortens time to publication, which makes the journal look more desirable. If authors are asked to revise the paper, it is usually seen by the same reviewers. If the revisions satisfy the editor, the paper will get accepted. From there, it is a variable period of time before the paper ends up online. This whole process takes a lot of time, which the journal mostly gets for free from academic editors and peer reviewers. Academics don’t know how to value their time.

With this stage set, we will talk next week about the money faucet called Open Access and how Europe is trying to destroy academia.